Climate change is something your students will unfortunately have to battle in their lifetime. But how can you prepare them without freaking them out? Have you ever stumbled trying to talk about climate change in your science classroom?

Despite the fact that an overwhelming majority of scientists link climate change to human activity, the causes of global warming remain a contentious topic in the political arena. Between the scientists who label it as a fact that our choices are leading to devastating results (coastal cities underwater, extinction of animals and plants), and certain politicians who say that humans are not to blame, educators can find themselves in a tough position when having to talk to their students about climate change.

Sticking to scientific facts

When talking to students, you can avoid entering the political arena of unsubstantiated claims about the environment by sticking to scientific facts which link the trends of human activity and climate change:

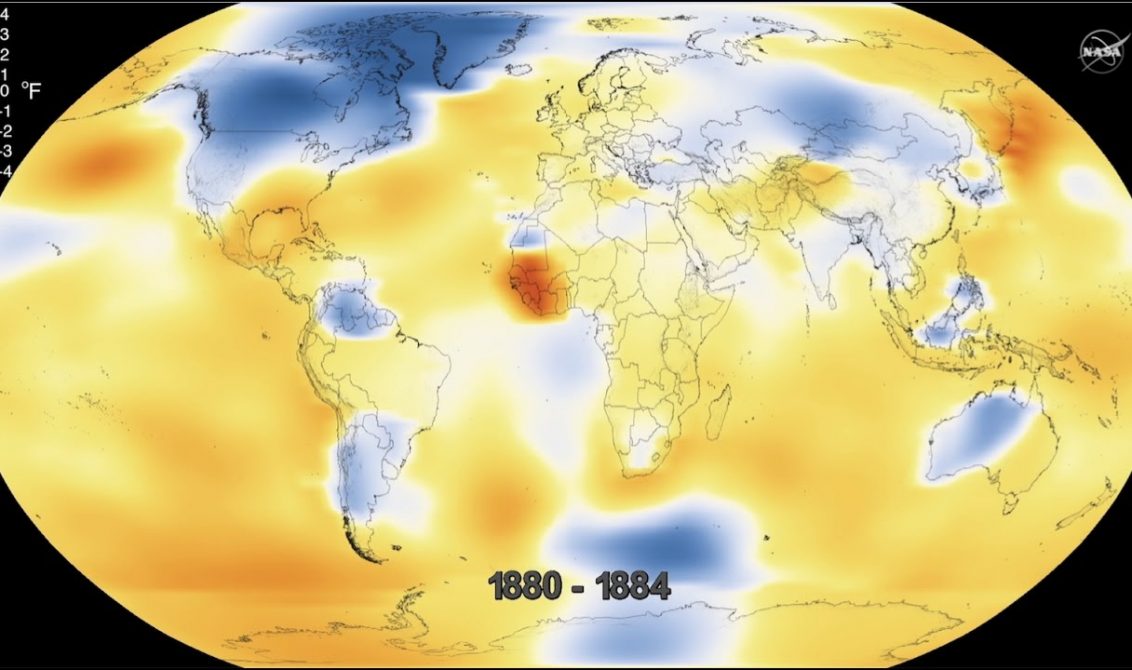

Globally, the year 2016 was the 3rd year in a row with record high surface temperature: Earth’s average surface temperature has risen about 2.0 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 19th century, largely a result of human emissions into the atmosphere. There once was a time when people argued about the reliability of ground weather stations, unbalanced sampling, urban warming effects, etc. No more. The satellites map the whole globe continuously. We know exactly what is happening at all times. Satellites also monitor the melting of ice, which is accelerating globally.

Five years ago Greenland and Antarctica together were melting ice at a rate of 200 billion tonnes per year. That rate is now 350 billion tonnes per year.

Satellites track the rise in sea level as ice melts and the ocean water warms. Not long ago the seas were rising at 2 mm per year. Now it is over 3 mm per year. And that rate of rising continues to increase. A phenomenon called “sunny day flooding” is now occurring up and down the eastern U.S. coast. Without any storms or rain, high tides are now flooding many roads and communities.

We understand the physics of the greenhouse effect. The more than 9 billion tonnes of carbon released into the atmosphere each year from the burning of fossils fuels has increased the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide to more than 400 ppm. This is nearly a 50% increase over pre-industrial levels, and is a direct result of our insatiable energy consumption of 18 trillion joules per second (btw, if humans had to physically generate these 18 trillion watts of power themselves, it would require every man, woman, and child in the world bench-pressing about 570 pounds every second, over and over, 24 hours a day).

Data: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Some description adapted from the Scripps CO2 Program website, “Keeling Curve Lessons.”

These are facts. As George Carlin used to say, you can’t have opinions about facts. The point of all this is that climate change is not a hoax. Increasing the burning of coal will have significant global impacts. Just look at the data provided by NASA’s satellites.

How can you start to talk to your students about climate change?

For younger students (K-2), you can help them think about what steps they, their families, and their schools can take to help take care of the Earth (recycling, re-using materials, limiting waste, using re-usable containers, choosing renewable materials, etc.). As they get older, they can think bigger, brainstorming ways they can influence their local, state, and national government in developing policies that can have a positive effect on the earth. For students in grades 3-5, consider a lesson on the science behind the greenhouse effect, and how both natural factors (i.e. volcanoes that release ash and other particles that block sunlight) and human activities (i.e. burning fuels for heat, transportation, or electricity where carbon dioxide is produced) change the climate.

For older students who may know more about the political debate about the causes of climate change, have a discussion about the difference between facts and opinions. Then present the facts to them and have them come up with ideas of their own on how to solve the climate change crisis (e.g. Carbon tax? Global emissions agreement? Technological change?). It’s never been more important to tap into the ideas of students who may soon be the future leaders of our world.

Continue Reading: Climate Change and Hurricanes

About the author

Michael E. Wysession is a Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and author of numerous science textbooks published by Pearson Education.